By Zoe Ann Stoltz, Reference Historian

Montana Historical Society resources—from newspapers to diaries and letters to blogs—not only document the many milestones achieved by Montana’s women legislators, they also promote a deeper understanding of the inherent sexism faced by Montana’s pioneer female elected officials.

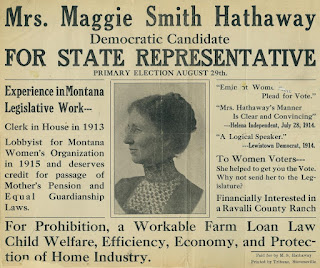

Montana Legislative Women (MLW) have been making history since rancher Maggie Hathaway and journalist Emma Ingalls walked into the House Chambers in 1917–Hathaway was a Stevensville Democrat; Ingalls was a Republican from Kalispell. Both women left important legacies. Ingalls chaired the House committee on Morals, Charities, and Reform while sponsoring HB 374, which created a separate vocational school for women. Hathaway introduced HB 63, which required local institutions to hire female attendants for female prisoners; HB 258, which detailed procedures for committing students to the School for the Deaf and Blind in Boulder as well as purchasing of a farm for the School; and HB 383, which required fire escapes for all multi-floored Montana schools. Hathaway’s Democratic colleagues elected her minority floor leader, the first woman in the country to hold such a distinction. She later acted as the Director of the Montana Bureau of Welfare. Both women participated in the ratification of Suffrage Amendment during the 1919 Extraordinary Session.

During the period between 1917-1939, twelve women joined the MLW. That number doubled from 1941-1971, when twenty-four women served in Montana’s Legislature. MLW members continued to make history. Elected in 1932, Wolf Point’s Dolly Cusker Akers was the first Native American to serve in the Montana House of Representatives. Mabel Cruickshank became the first women elected to the legislature from Gallatin County in 1936. An education advocate, she sponsored a bill creating adult education classes and schools throughout the state. Ellenore Bridenstine entered the state senate chamber in 1945, the first woman to serve in Montana’s upper chamber.

Participation in the Montana Women’s Caucus, the League of Women Voters, and the 1972 Constitutional Convention, prepared a new generation of women to tackle the male dominated state legislature. In 1973, nine women served. The 1975, 1977, and 1979 sessions each had fourteen women. Their names are familiar to many—Betty Babcock, Pat Regan, Dorothy Bradley, Ora Polly Holmes, and Aubyn Curtis, to name a few. Air Force wife Geraldine Travis from Great Falls was Montana’s first African American legislator. When asked about her priorities, she explained, “I believe in Black rights, women’s rights, children’s rights—human rights and dignity.”

1970s MLW members played integral roles in bringing Montana laws in line with the new constitution. Victories included the addition of the clause “irreconcilable differences” as reason for a divorce, acts to prevent sexual discrimination in the work place, creation of laws preventing the discharge of a female employee due to pregnancy, and use of more inclusive language in lawmaking. Results of the latter included allowing women to be legal head of households, forbidding institutions to deny credit to a person based on gender, and redefining rape as assault on one person by another, rather than the narrow belief that rape was a man assaulting a woman.

MLW members discovered that as they battled discriminatory legislation, they also battled decades of poor behavior. For example, not until 1978 did Montana’s legislative women get a private restroom. From 1917 to 1979, MLW members watched their male counterparts take advantage of a private lavatory, often using the facility to avoid lobbyist. During this time, female legislators faced a gauntlet of lobbyists and press as they made their way to public restrooms. It was not until 1979 that they received a modicum of privacy with the installation of partitions; their bathroom situation further improved with the appropriation of monies for permanent facilities to accommodate their needs.

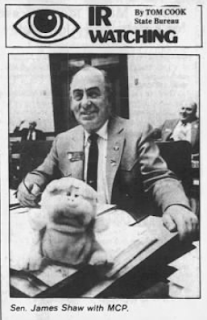

On the other hand, in 1985, Billing’s Senator Pat Regan took a humorous approach to bring attention to uncensored sexist remarks made by her fellow state senators. She kept a pink pig, labeled “MCP”—Male Chauvinist Pig—on her desk. When colleagues made sexist remarks, such as referring to staff as “gals” or “girls,” she had one of the pages deliver the MCP to their desk. One beneficiary earned the MCP by remarking that a woman murdered by her husband may have deserved it.

While the 2019 numbers did not break the record held by the 2015 legislature with forty-seven women, the percentage of Montana Legislative Women grows consistently. Each woman brings her own passions and style. They must be successful, because I have not heard the term “Male Chauvinist Pig” in quite some time.

For more information see:

- Women’s History Matters particularly Montana Women’s Legal History Timeline

- Digitized Montana Newspapers online

- Montana Newspapers on microfilm

- Montana Research Center catalog

- Waldron, Ellis, Montana Legislators, 1864-1979, Profiles and Biographical Directory, Missoula, Bureau of Government Researcher, 1980

- MC 180 Montana League of Women Voters, MHS Archives, Helena, MT

- RS 22 Montana Constitutional Records, 1971-1972, MHS Archives, Helena, MT