By Matthew M. Peek, MHS Photograph Archivist

In his State of the Union address in January 1964, President Lyndon B. Johnson declared a “war on poverty.” Speaking on March 18, 1964, just after a major bill to fight poverty was introduced to Congress, Montana’s U.S. Senator Lee Metcalf expressed his deeply held support:

Only a small fraction of our nation’s poor are wholly responsible for their condition. Most often they are the victims of circumstances. Just as some Americans inherit wealth, others are born into poverty. . . . Somehow, we must find a way to break the cycle of poverty that so frequently carries from father to son. The elimination of poverty is above all a moral obligation.In July 1964, with a vote of 61 to 34, the U.S. Senate passed Senate bill 2642, its version of the Economic Opportunity Act of 1964. The U.S. House passed the bill a couple weeks later and President Johnson signed the bill into law on August 20, 1964. Johnson’s “War on Poverty” was launched with this act, signaling a national dedication to the eradication of poverty in the United States through the provision of “opportunity.” The Economic Opportunity Act would become the hallmark of Johnson’s administration.

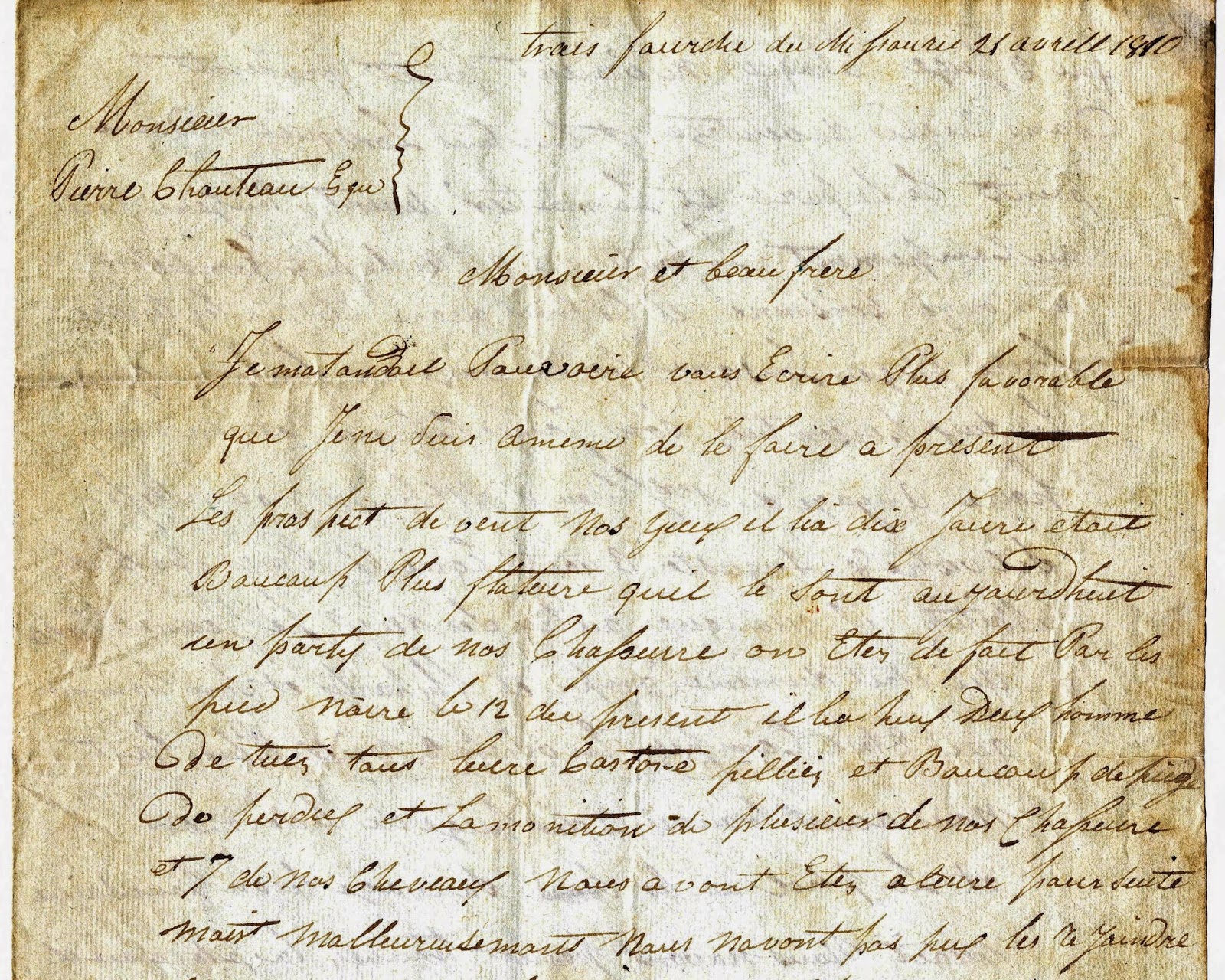

|

| MHS Photo Archives, Lot 31 B8/14.04: Great Falls School District speech therapist Jean Irwin (right) works with Lily Meyer, a participant in Head Start, in Great Falls, Montana, [circa 1960s]. |

What few people realize is this ground-breaking legislation had its origins in the patient work of Montana’s Lee Metcalf, first as a representative to Congress in the 1950s, and later as a U.S. Senator in the 1960s. Working closely with his friend and colleague Senator Hubert H. Humphrey (D-MN), then Representative Metcalf envisioned a program for youth patterned on the 1930s Civilian Conservation Corps, which he and Humphrey called the Youth Conservation Corps (YCC). The idea behind the program was to help lower youth delinquency through federally-funded summer forest, park, and wilderness conservation and improvement programs. The program allowed for “enrollment of up to 150,000 boys and young men, between the ages of 16 and 22.”

On December 29, 1956, Senator Humphrey unveiled the first version of the YCC, in a six-point youth opportunity program to address education, delinquency, and employment for youth and college students in America. On behalf of his colleague, Rep. Metcalf, Montana Senator James E. Murray introduced a bill (S. 812) he wrote for the establishment of the YCC in 1959, based on Humphrey’s proposal. Despite setbacks, Humphrey and Metcalf would continue to work from 1956 to 1964 for passage of America’s most sweeping social welfare programs.

Metcalf testified with Senator Humphrey before a House of Representatives Education Subcommittee in April 1960 regarding the situation in which young boys and men found themselves after World War II. Referring to the constant flow of youngsters into the labor market which he said “is at best inhospitable to teenagers,” Metcalf declared,

Many of these youngsters . . . are not going anywhere, except to boredom, confusion and trouble. Evidence of this is provided by the growing problem of juvenile delinquency—and the increasing numbers of youngsters in our custodial and penal institutions.The program failed in the U.S. House in 1960. Nothing happened with the bill until February 14, 1963, when President John F. Kennedy gave a “Special Message to the Congress on the Nation’s Youth.” He called for solutions to deal with the growing issues faced by America’s youth.

After years of work, Metcalf was ready to make the final push. By 1963, he had become a U.S. Senator involved with Senate committees dealing with education, public works projects, and the Interior Department. Senator Metcalf helped strategize and publically campaigned for the establishment of a series of national social welfare programs, trying to address rising social problems across the country.

After ascending to the presidency following Kennedy’s assassination, Lyndon Johnson moved to capitalize on the years of preparation when he called for his “war on poverty.” The President’s poverty program was multifaceted. Along with an authorization for nearly a billion dollar appropriation to implement the proposed act, the bill called for the creation of the following: a Jobs Corps; work-training programs; a federal college work-study program; community action programs; rural areas programs; employment and investment incentives; a version of the Peace Corps for the United States, labeled the Volunteers in Service to America, or “VISTA”; and experimental or demonstration programs labeled “Family Unity Through Jobs.” The bill would also create the Office of Economic Opportunity, whose Director would hold the power to define broad portions of the act and delineate funds for various programs.

It is the constitutional responsibility of Congress to provide for the general welfare. The Economic Opportunity Bill of which I am a sponsor and which passed the Senate this last week is designed to help fulfill that responsibility. . . . I am proud to have had a part in its inception.Following the bill’s passage, Metcalf worked to establish and get funding for Head Start programs in Great Falls, Montana, Job Corps Camps at Kickinghorse on the Flathead Indian Reservation, neighborhood centers, and Neighborhood Youth Corps programs in Butte, Montana, among many others.

Despite the War on Poverty’s ultimate failure to fulfill its grand scheme, the legislation did and does still bring great benefit to the United States and Montana. Senator Lee Metcalf’s role in laying the groundwork for the Economic Opportunity Act of 1964 was not in vain, and his steady and active drive to pass it marks him as one of America’s great social welfare legislators.

.jpg)