State Historic Preservation Office

Scourges including smallpox, typhoid fever, and contaminated drinking water ravaged the West’s inhabitants. Disease impacted many of Montana’s settlements, and left particularly devastating and lasting impacts on tribal nations. Like COVID-19 today, diseases throughout Montana’s history disproportionately impacted native people. Despite the need, Congress did not codify provisions for health care to all federally recognized nations until the Snyder Act of 1921.1 No statewide public health entity existed in Montana until 1901, when the Legislature established the Montana State Board of Health.

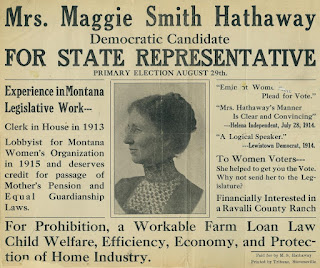

Between 1864 and 1901, Montana laws vested the responsibility for public health to local jurisdictions, but retained a few basic health-related laws. The 1866 Montana Territorial Legislature exempted “all squares and lots dedicated or kept open for health” from taxation. A year later, the Civil Practice Act deemed “anything which is injurious to health…the subject of an action.” Child’s Health Primer sat on every school’s bookshelf, and the state seated a Board of Examiners to regulate and certify medical practitioners by 1889. Municipalities could appoint local health boards and establish quarantines, and by 1895, Montana Codes provided that the state could detain people on the grounds of public health. Montana’s 1895 laws also codified the establishment and duties of County Boards of Health to guard against contagious or infectious diseases.2

Montana’s Seventh Legislative Assembly created the State Board of Health of Montana (BOH) in 1901. The Board had “the general care of the sanitary interests of the people” and authorized “sanitary investigations and inquiries respecting the causes of disease, and especially epidemics, the causes of mortality and the influence of locality, employment, habits, and other circumstances and conditions, upon the health of the people.”3 Concerns included Rocky Mountain spotted fever; tuberculosis; food and drug safety; storm sewers; infant, maternal and child health; a lack of local health officials; and sanitation in schools, at tourist facilities, and on passenger trains. Over the next few decades, the BOH expanded to multiple divisions and oversaw advancements in many areas including research, epidemiology, sanitation, licensing, and public health education.4

Rocky Mountain spotted fever particularly concerned officials and residents during the first decades of the twentieth century, and research into the disease concentrated in the Bitterroot Valley. The BOH sanctioned research there beginning in 1901, and work progressed with fits and starts through the 1910s. Efforts included tick collection, eradication, and vaccination. The researchers worked from tents, rented houses, and other makeshift labs until 1928, when the BOH used state funds to construct the Montana Board of Entomology Laboratory in Hamilton. The federal Public Health Service purchased the laboratory in 1932, renaming it Rocky Mountain Labs (RML). The National Institutes of Health (NIH) took control in 1937. RML staff worked to help prevent and treat military personnel from spotted fever, typhus, and yellow fever during World War II. RML continues to function as one of the nation’s most important research and vaccine production facilities.5

After World War II, public health research expanded at the state’s universities as well. During the late 1950s, scientists at Montana State College (later Montana State University–Bozeman) agitated for a new laboratory to support medical research. Funded in part with state money and a grant from the NIH, the Medical Science Wing, later named Cooley Laboratory, opened in 1960. The biomedical research programs at MSU continue to expand including Microbiology and Immunology, Cell Biology and Neuroscience, and pre-Medical studies. At the University of Montana–Missoula, the School of Pharmacy began in 1907, and a broader Science program initiated during the 1930s. UM’s College of Health added programs through the late twentieth and early twenty-first centuries, including Physical Therapy and Rehabilitation, Center for Environmental Health Services, the Center for Structural & Functional Neuroscience, Social Work, Family Medicine Residency, and Neural Injury Center.6

The BOH oversaw the state Department of Health established in 1967, and both entities added Environmental Services to their name in 1971. The Board existed until 1994. A year later, the Department of Health restructured together with the state Department of Social and Rehabilitation Services to become Montana’s Department of Public Health and Human Services (DPHHS). The Department operates from historic buildings on the Capitol Campus in Helena, including the DPHHS (formerly SRS) building, and the Cogswell Building.

Historic places throughout Montana continue to serve important roles in public health. During the COVID-19 pandemic, county health offices, together with state and federal entities worked together gathering data, conducting research, providing educational materials, and distributing vaccines. Statewide, herculean efforts to combat disease and promote public health persist, and challenges continue to arise.

ENDNOTES

- BL Shelton, “The Legal and Historical Roots of Health Care for American Indians and Alaska Natives in the United States,” Issue Brief. (Menlo Park, CA: The Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation, 2004), p. 7; 42 Stat. 208; Jeffrey Ostler, “Disease Has Never Been Just Disease for Native Americans,” The Atlantic, April 29, 2020; Donald Warne and Linda Bane Frizzell, “American Indian Health Policy: Historical Trends and Contemporary Issues,” American Journal of Public Health, 2014 June; 104 (Suppl 3): S263–S267. ↩

- Laws of the Territory of Montana Passed at the Third Session of the Legislature, 1866, Chapter II, Section 4, (Virginia City, MT: Jno. P. Bruce, Public Printer, 1866), p. 10; General Laws and Memorials and Resolutions of the Territory of Montana Passed at the Fourth Session of the Legislative Assembly, 1867, Title VIII, Chapter 1, Section 249, (Helena, MT. : State Pub. Co, 1915), p. 187; “An Act to Regulate the Practice of Medicine in the Territory of Montana,” and “School Text Books,” Laws, Resolutions and Memorials of the Territory of Montana Passed at the Sixteenth Regular Session of the Legislative Assembly, 1889, (Helena, MT: Journal Pub. Co., Public Printers, 1889), pp. 175-178 and 212; DS Wade et al., “Political Code of Montana,” The Codes and Statutes of Montana: In Force July 1st, 1895, Title I, Chapter III, Section 50 (Butte, MT: Inter Mountain Publishing Co., 1895), p. 14. ↩

- As quoted in Montana State Board of Health, 26th Biennial Report, 1950-1952: Marking 50 years of Service in Guarding, Improving, Montana’s Health, Helena, MT, 1952. ↩

- Jessie Nunn, “Board of Health Building,” Montana Historic Property Record Form, 2013, on file at MT SHPO, Helena. ↩

- “History of Rocky Mountain Labs (RML),” National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases website, n.d., accessed May 11, 2021. https://www.niaid.nih.gov/about/rocky-mountain-history. ↩

- Jessie Nunn, “Medical Science Research Building (Cooley Labs),” “Social and Rehabilitation Services Department Building (DPHHS),” “Board of Health Building,” Montana Historic Property Record Forms, 2013 and 2015, on file at MT SHPO, Helena. ↩

PUBLIC ARCHITECTURE

2021 MONTANA PRESERVATION POSTER

Montana SHPO's final Montana Preservation Poster celebrates the state’s public health history, featuring Rocky Mountain Laboratories in Hamilton. Montana has been a leader in public health since the turn of the 20th century, when entomological research became concentrated in the Bitterroot Valley. In 1928, the state constructed “Building 1” at what would eventually become Rocky Mountain Laboratory (RML). During World War II, the laboratory produced vaccines to protect soldiers against spotted fever, typhus, and yellow fever. Today, scientists at RML investigate a wide variety of infectious diseases, including COVID-19.

To order your free Montana Preservation Poster, send an email with your mailing address and poster selection to Melissa.Munson@mt.gov, or call (406) 444-7715.

https://mhs.mt.gov/Shpo/NationalReg/PreservationPoster