It seems only fitting that the third largest moving image collection at the Montana Historical Society documents the professional career of Lee W. Metcalf, one of the state’s most industrious public servants. Between the years 1937 and 1952, Metcalf served as a Montana state congressman, state assistant attorney general, World War II soldier and military prosecutor, and a Montana Supreme Court Associate. From 1953 to 1961, he held Montana’s First District United States Representative seat, and in 1962, he became the first Montana native to serve his home state in the U.S. Senate. His career as a Democratic senator was distinguished by a long list of progressive measures, many of which were related to conservation and environmental protection legislation. In addition to his passion for regional and national ecological concerns, Metcalf was also known for turning his attention to a host of complex societal issues such as health care, veterans’ rights, consumer protection, public education, firearms, and poverty. Metcalf served Montana in the U.S. Senate until his death on January 12, 1978 and was ranked number 15 on a list of the 100 Most Influential Montanans of the Century by The Missoulian in 1999.

Given the progressive nature of his political endeavors and his desire to reach the voting public en masse, it is no surprise that Metcalf’s office was responsible for the creation of a large volume of motion picture films and videotapes. The Lee Metcalf moving image collection at the Historical Society consists of 388 reels of 16mm film, with an additional 38 items on various video and digital formats. These 426 items pertain directly to Metcalf’s political endeavors between 1959 and 1973, and his work in both the House and the Senate is represented within these documents. Campaign commercials with twenty, thirty, and sixty second running times were recorded by Metcalf and his team, and the themes of these advertisements give us a clear idea of the policies that he was addressing with his constituents: education, farming, industrial and small business development, social security, unemployment, taxation, and conservation, to name a few. Certain commercials also feature endorsements by like-minded politicians in Washington, D.C., and these films show strong support for Metcalf from such prominent figures as Senators’ Mike Mansfield and Edward Kennedy and Vice President Hubert Humphrey. The collection also contains various speeches given by Metcalf during this period, with appearances being filmed both inside and outside of Montana.

|

From Metcalf’s “Washington Report” of May 12, 1966 (Lot 31)

|

The bulk of the items in the Metcalf moving image collection represent installments in a series of television films created by the politician’s team during his time in the Senate, the purpose of which were to inform constituents of current political issues via mass media. “Report from Washington” (1963-1965) and “Washington Report” (1965-1967) feature Metcalf addressing the camera in an office setting, and often in conversation with a political contemporary who has detailed knowledge of the subject at hand. Topics of conversation in this series are as far-reaching as those found in his campaign films, and the participants regularly discuss specific policies and pieces of legislation: Medicare, Minuteman-II missile production, Peace Corps, the Economic Opportunity Act, and the Veterans’ Readjustment Act. The issues directly related to Montana are often environmental in nature, including the creation of Bighorn Canyon Recreation Area, the building of Libby Dam, increased protection of migrating waterfowl, and the Great Plains Conservation Program.

|

Production script from 60 second commercial

MC 172, Box 646, Folder 3

|

|

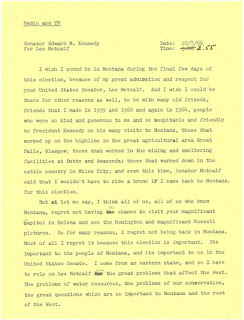

Script from Kennedy endorsement commercial

MC 172, Box 646, Folder 3 |

As with many of the items in the moving image archives, the content of Metcalf’s films can be greatly enhanced by information from other collections within the Historical Society. The Lee Metcalf photograph collection contains over 3,500 items, many of which similarly record his extensive political career. We also have access to a wealth of textual information related to the senator’s films in the Lee Metcalf papers, a collection which boasts over 300 linear feet of documentary material. Copies of recorded speeches, scripts of political endorsements, detailed information on general campaign commercials, transcripts from the “Report from Washington/Washington Report” television films, and even teleprompter printouts from televised addresses can all be found within these files. Such items provide a meaningful window into the production process undertaken by Metcalf and his staff, thus giving us an idea of just how much work went into the completion of a single film.

|

Section of a teleprompter script

MC 172, Box 646, Folder 3 |

Several items from the Metcalf collection have now been digitized, and a selection of these films can be seen on the MHS moving image archive YouTube channel and in the Research Center reference room.