Every

spring, the MHS Research Center offers two James H. Bradley Fellowships to graduate students, faculty, and/or independent scholars

pursuing research on Montana history.

Past recipients and topics reflect the dynamics of Western U.S.

historical interests, from Native women’s work wages/opportunities to Lee

Metcalf’s role in environmental politics. The naming of the fellowship was no

accident. Rather, its title represents just a hint of the invaluable legacy

left to Montana by Lt. James Bradley, an historian who collected, created, and

carried history.

|

| James H. Bradley, 1st Lt. 7th U.S. Infantry [no date] MHS Photo Archives # 941-317 |

Born in Ohio in 1844, James H. Bradley served in the Ohio

Volunteer Regiment during the Civil War. Following the war, he reenlisted and

was quickly promoted to First Lieutenant. From 1866 through the next eleven

years he was stationed primarily in Wyoming, Utah and Montana Territories. His deployments consistently put him in harm’s

way. During a brief 1871 assignment in Georgia and Alabama to suppress the

escalation of Ku Klux Klan activities, he met and married Mary Isabella Beach.

He returned to Montana with his new bride in January 1872. The couple was stationed at Fort Benton and Fort Shaw until 1877.[1]

The developing Montana Territory and its major players consumed much of Bradley’s spare time. He studied historical resources, such as volumes of the 1872 “History of the Expedition under the Command of Captains Lewis & Clarke." Bradley sought out and recorded stories told to him by early Montana history makers including Alexander Culbertson, one of the founding fathers of Fort Benton. He created historical sketches of Crow, Gros Ventre, Blackfoot and Sioux [2].

While under the command of General Gibbon, Bradley detailed daily events of the 1876 campaign against the Northern Cheyenne and Lakota. As Commander of the Scouts, including 23 Crow and two white, Bradley had the unenviable duty of repeating the Scouts’ report to Gibbon of a “horrid” battle involving Custer. Bradley’s final journal entry, dated Monday, June 26, conveys the reactions prompted by the report. Less than 24 hours later, Bradley and his scouts discovered the remains of Custer and his men.[3]

Bradley himself died on August 9, 1877, during the Battle of the Big Hole. Bradley’s passion for Montana history did not die with him, though. Upon the news of his death, Mrs. Bradley sold several of her husband’s books to trader J.H. McKnight. She then packed the bulk of Lt. Bradley’s writings and took them with her as she arranged passage back to Atlanta, Georgia aboard the steamboat Benton.[4] Just two years later, in 1878, she sold the collection to the Montana Historical Society. [5]

One hundred thirty-six years later, Bradley’s legacy, both literally and figuratively, lives on at the Montana Historical Society Research Center. The numerous journals which he carried, such as the handwritten journal of the 1876 “Sioux Campaign on the Yellowstone,” along with The James H. Bradley Papers, 1872-1877 (Manuscript Collection 49), are retained in the MHS archives.

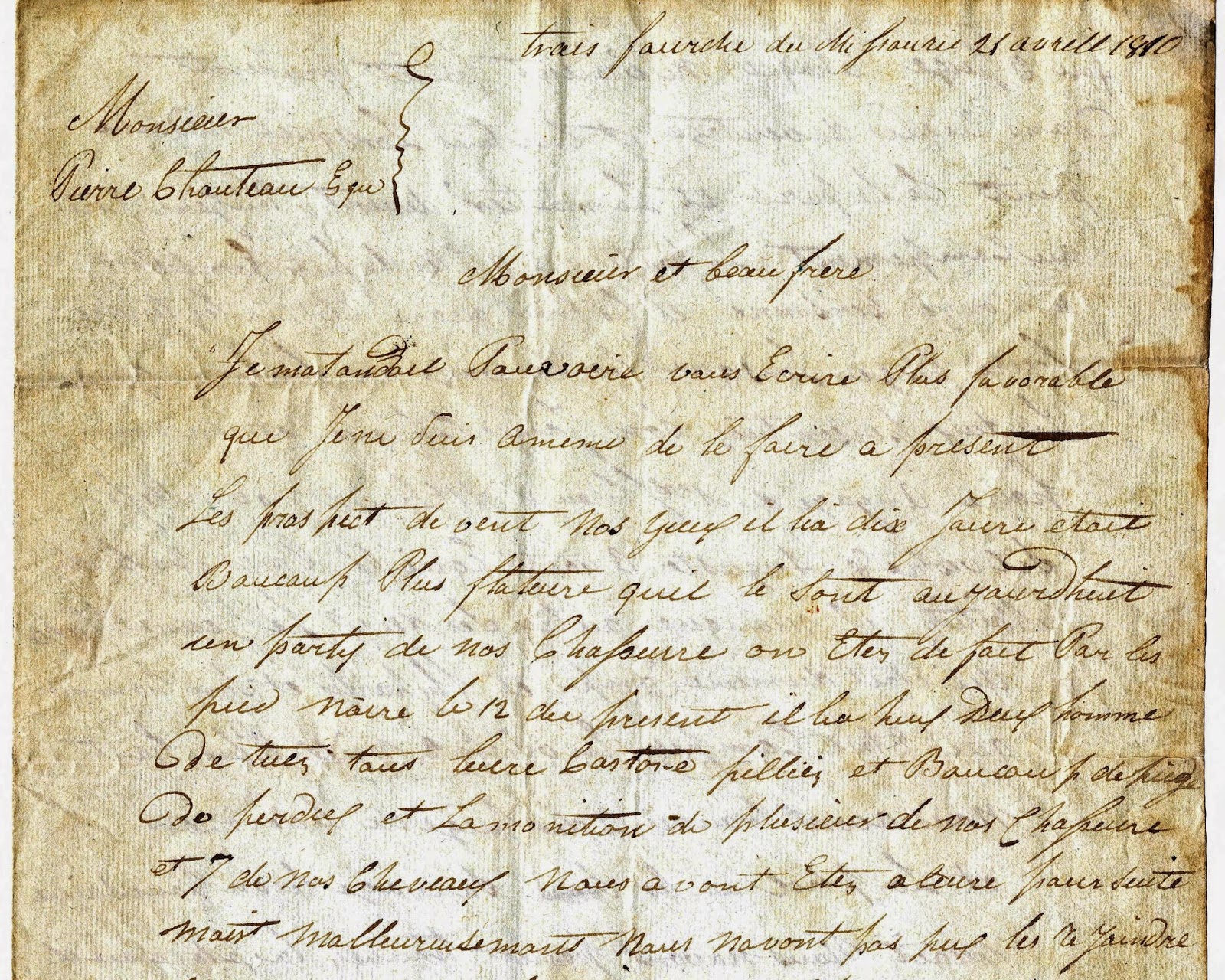

A few books from his personal library are housed in the MHS library's collection, including both volumes of "History of the Expedition under the Command of Captains Lewis & Clarke," which Bradley signed and dated after picking them up in Fort Benton Feb. 21, 1874.[6] The volumes, small enough to fit in an inside pocket or saddle bag, still evoke the smell of camp fires.

This spring, the MHS Research Center will once again accept Bradley

Fellowship applications. The Fellowship is just one of many

legacies left by Lt. James Bradley’s passion for Montana’s history.

|

| Bradley's signature in his personal copy of "History of the Expedition under the Command of Captains Lewis & Clarke" |

____________________________________________________

[1] Jon G. James, “Lt. James H. Bradley, The Literary Legacy of Montana’s Frontier Soldier-Historian,” Montana, the Magazine of Western History, Winter 2009, v. 59, no. 4: 46-57.

[2] James H. Bradley Papers, 1872-1877, MC 49, Box 2, Folder 10.

[3] Lt. James H. Bradley, The March of the Montana Column, A Prelude to the Custer Disaster, ed. Edgar I. Stewart (Norman, OK: University of Oklahoma Press, 1961), 153-162.

[4] "Mrs. Bradley,” The Benton Record, August 17, 1877, p. 3.

[5] Jon G. James, 56.

[6] Meriwether Lewis, History of the expedition under the command of Captains Lewis and Clarke : to the sources of the Missouri, thence across the Rocky Mountains, and down the River Columbia to the Pacific ocean: performed during the years 1804, 1805, 1806, by order of the government of the United States, ed. Archibald M’Vickar, (New York: Harper & Brothers, Publishers, 1872). MHS Library Locker 917.8 L58HM 1871, Vol. 1 & 2.

[2] James H. Bradley Papers, 1872-1877, MC 49, Box 2, Folder 10.

[3] Lt. James H. Bradley, The March of the Montana Column, A Prelude to the Custer Disaster, ed. Edgar I. Stewart (Norman, OK: University of Oklahoma Press, 1961), 153-162.

[4] "Mrs. Bradley,” The Benton Record, August 17, 1877, p. 3.

[5] Jon G. James, 56.

[6] Meriwether Lewis, History of the expedition under the command of Captains Lewis and Clarke : to the sources of the Missouri, thence across the Rocky Mountains, and down the River Columbia to the Pacific ocean: performed during the years 1804, 1805, 1806, by order of the government of the United States, ed. Archibald M’Vickar, (New York: Harper & Brothers, Publishers, 1872). MHS Library Locker 917.8 L58HM 1871, Vol. 1 & 2.

.jpg)

.jpg)